Design Spotlight

European Robin Hood: A Birdorable Blend of Nature and Folklore

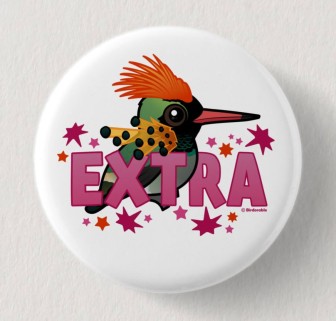

This week we're shining a spotlight on one of our newest designs, featuring our European Robin. The European Robin Hood design is a playful blend of nature and folklore, combining the cute charm of the European Robin with the legendary Robin Hood. This adorable bird dons a classic bycocket hat, a medieval-style cap with a turned-up brim and a feather—an iconic look often associated with Robin Hood. The design captures both the whimsy of the natural world and the adventurous spirit of one of England's most famous folk heroes.

The European Robin is a beloved songbird found across the continent, recognized for its bright orange-red breast and friendly nature. In folklore and tradition, it is often seen as a symbol of joy and good luck. This little bird has a bold personality, sometimes even approaching humans in gardens and woodlands. With its inquisitive nature and bright appearance, the European Robin is a perfect match for the legendary outlaw who roamed Sherwood Forest.

As an aside, did you know that the American Robin was named by European settlers who were reminded of the beloved European Robin, often called "Robin Redbreast," due to its similar shape and reddish-orange breast? Despite the resemblance, the two birds are not closely related. The European Robin belongs to the flycatcher family, while the American Robin is a member of the thrush family. The name "robin" stuck, even though the American Robin is larger and behaves more like a true thrush than its European namesake.

Robin Hood’s story has been told for centuries, evolving from medieval ballads to books, films, and TV shows. The folk hero is famous for standing up against injustice, stealing from the rich to help the poor, and outwitting the corrupt Sheriff of Nottingham. Along with his band of Merry Men, he became a symbol of resistance and fairness, inspiring countless adaptations and retellings. His signature bycocket hat, often made of felt or leather and featuring a feather, has become one of the most recognizable elements of his look, and makes our cartoon character instantly recognizable.

Our European Robin Hood design is a fun and creative way to celebrate both birds and folklore. Whether you’re a bird enthusiast, a history buff, or a fan of Robin Hood’s legendary exploits, this adorable bird-as-folk-hero design is sure to bring a smile to your face. Available on a variety of products, including t-shirts, hoodies, pillows, and tote bags, it makes a great gift for anyone who loves birds or enjoys a good tale of heroism and adventure.

Embrace the spirit of the forest and add a little medieval flair to your bird-loving world with this delightful Birdorable creation!